Why should I care about the gut-brain axis? Part 2 - Gut-brain axis: how does it influence brain health?

The gut- brain axis is a two way communication hub between two of the most important organs in the human body. Facilitated by a physical connection via the vagus nerve and a wireless one via hormones and neurotransmitters, the axis enables the brain to influence your intestinal function and vice-versa.

And that’s the focus of this second part of our three part series of the gut-brain axis and why you should care.

So, sit tight, things just gut interesting!

The gut-brain axis and mental health

The close inter-connection between the gut and brain is fundamental in health and disease. The gut-brain axis is associated with regulating a stable internal environment to help support the daily bodily functions, but if it becomes off kilter then it can affect both physical and mental health.

How gut microbes can influence your mental health

When the gut microbiome is balanced, called eubiosis, the intestinal environment is stable, there is a rich abundance of commensal and symbiotic microbes, working hard to keep the body healthy.

Gut microbes are responsible for transforming the dietary fibre you eat into tiny forms of magic AKA short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and vitamins.

SCFAs, specifically acetate, butyrate, and propionate have major benefits for your intestinal health as well as your mental health, energy intake and inflammatory status. The greater the abundance of commensal microbes in the gut, the greater their activity and the stronger your gut barrier will be.

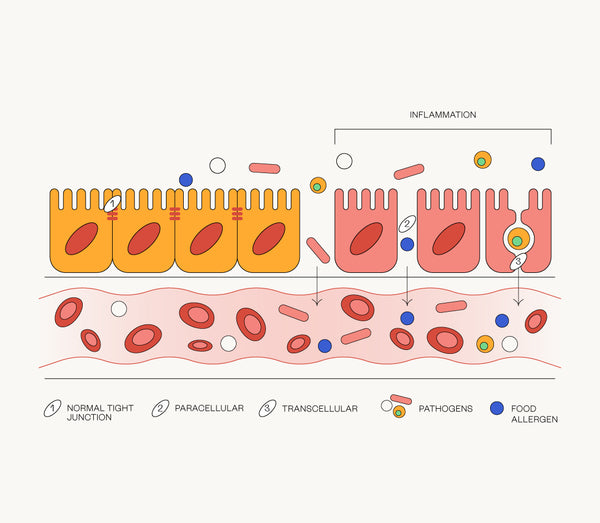

The gut barrier is a strong defensive wall which has small gaps called tight junctions that are responsible for preventing toxins, partially digested food and pathogens from entering the bloodstream and wreaking havoc. But they also allow the absorption of vital nutrients, they’re like security for the human body [1].

However, if these tight junctions become weak and the permeability increases, the nasty things the gut barrier usually stops from entering the bloodstream, leak through. It’s a phenomenon called leaky gut syndrome.

The problem with a leaky gut is that it is damaging for the central nervous system, causes inflammation, and is linked to mood disorders such as depression and anxiety [2].

When the permeability of the gut is weakened, gut bacteria enter the bloodstream and release toxic bacterial products called endotoxins. These endotoxins cause an inflammatory response from the immune system, causing the release of inflammatory proteins called cytokines.

Cytokines interrupt with the production of neurotransmitters like serotonin that are responsible for regulating your mood. If there is less serotonin being produced and released from the gut, then this sends negative messages via the gut-brain axis and results in negative moods and emotions as well as other symptoms such as fatigue.

Cytokines as well as the endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) play a role in the development of depression. Research shows that a leaky gut is associated with the inflammatory development of depression [3].

That’s not all, microbial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which enter the circulation from the gut and trigger an immune response, could be integral to the development of many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [4].

The gut-brain axis and inflammation key to mental health

The gut microbiome plays a significant role in the development of neuropsychiatric and mood disorders. A major explanation for this is the production of compounds like LPS, which cross the gut barrier and enter the bloodstream influencing brain function as well as the reduced production of neurotransmitters associated with regulating mood. These neurotransmitters send messages from gut neurons to brain neurons via the vagus nerve.

A dysbiotic gut is also an important factor. Remember, dysbiosis is where the gut microbiota is imbalanced and there is a greater abundance of pathogenic microbes and a lower abundance of beneficial bacterial communities.

If you have a balanced biome, the bacterial friends in your gut will be working hard to keep the tight junction proteins in the intestinal barrier functioning and preventing leakage of unnecessary nasties into the bloodstream. Plus, if they are happy and healthy they do wonderful things for your health.

For example, friendly bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, butyrate and propionate which keep your intestinal and mental health in check by lowering inflammation.

Butyrate is a major example. At Innate Co. we love butyrate! This SCFA is super exciting and is a real gift from your gut bacteria to you. So, what does it do?

There are heaps of functions that butyrate has within the body, which makes it such a valuable metabolite. So much so that it probably warrants a blog post all of it’s own. Hey, that’s an idea, stay tuned!

That said, butyrate helps to strengthen the gut lining, a fundamental factor in preventing toxins, pathogens, and other nasties from entering the bloodstream. The more diverse the gut microbiome, the more SCFAs including butyrate will be produced, and the stronger the integrity of the gut will be.

Watch this space for the third and final instalment of this series. We’ll be exploring why you should care about your gut-brain axis even if you’re healthy and what you can do to help keep it strong!

Sources

[1] Vancamelbeke, M & Vermeire, S. The Intestinal Barrier: A Fundamental Role in Health and Disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1343143 (2017)

[2] Ohlsson, L et al. Leaky gut biomarkers in depression and suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand 139. doi: 10.1111/acps.12978 (2019)

[3] Maes, M., Kubera, M & Leunis, J, C. The Gut-Brain Barrier in Major Depression: Intestinal Mucosal Dysfunction with an Increased Translocation of LPS from Gram Negative Enterobacteria (Leaky Gut) Plays a Role in the Inflammatory Pathophysiology of Depression. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 29. (2008)

[4] Houser, M, C & Tansey, M, G. The gut-brain axis: is intestinal inflammation a silent driver of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis? Npj Parkinson’s Disease 3. (2017)